Lambda pipelines for serverless data processing

You get tens of thousands of events per hour. How do you process that?

You've got a ton of data. What do you do?

Users send hundreds of messages per minute. Now what?

You could learn Elixir and Erlang – purpose built languages for message processing used in networking. But is that where you want your career to go?

You could try Kafka or Hadoop. Tools designed for big data, used by large organizations for mind-boggling amounts of data. Are you ready for that?

Elixir, Erlang, Kafka, Hadoop are wonderful tools, if you know how to use them. But there's a significant learning curve and devops work to keep them running.

You have to maintain servers, write code in obscure languages, and deal with problems we're trying to avoid.

Serverless data processing

Instead, you can leverage existing skills to build a data processing pipeline.

I've used this approach to process millions of daily events with barely a 0.0007% loss of data. A rate of 7 events lost per 1,000,000.1

We used it to gather business and engineering analytics. A distributed console.log that writes to a central database. That's how I know you should never build a distributed logging system unless it's your core business 😉

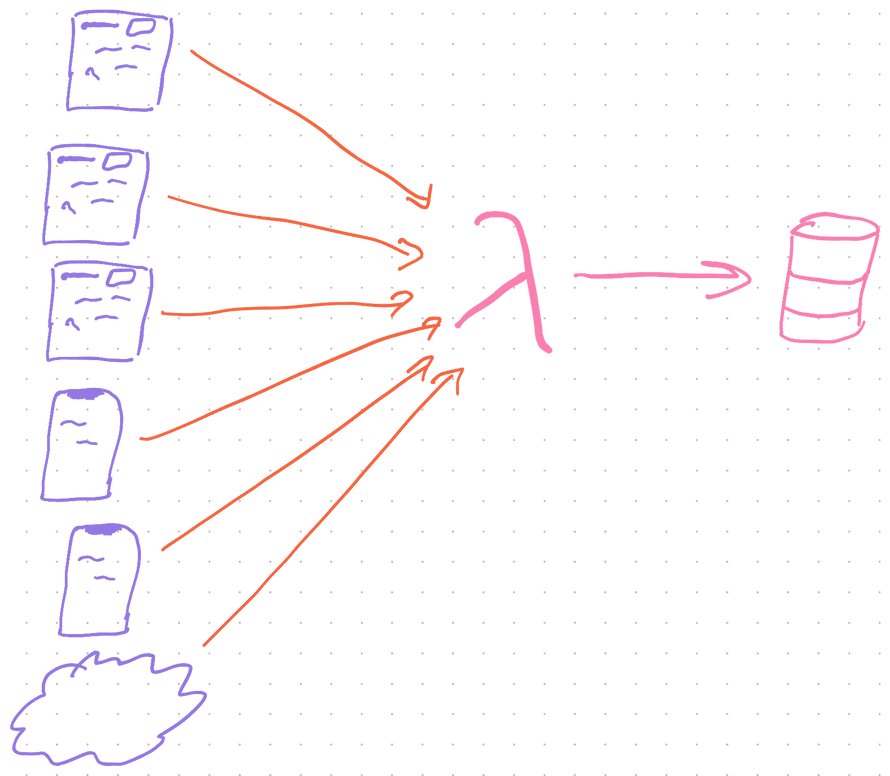

The system accepts batches of events, adds info about user and server state, then saves each event for easy retrieval.

It was so convenient, we even used it for tracing and debugging in production. Pepper your code with console.log, wait for an error, see what happened.

A similar system can process almost anything.

Great for problems you can split into independent tasks like prepping data. Less great for large inter-dependent operations like machine learning.

Architectures for serverless data processing

Serverless data processing works like .map and .reduce at scale. Inspired by Google's infamous MapReduce programming model and used by big data processing frameworks.

Work happens in 3 steps:

- Accept chunks of data

- Map over your data

- Reduce into output format

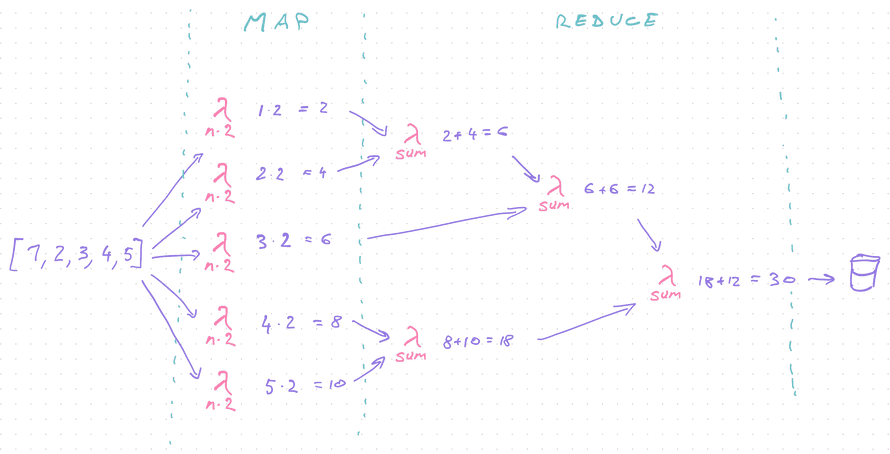

Say you're building an adder: multiply every number by 2 then sum.

Using functional programming patterns in JavaScript, you'd write code like this:

const result = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5] // input array.map(n => n * 2) // multiply each by 2.reduce((sum, n) => sum + n, 0) // sum together

Each step is independent.

The n => n*2 function only needs n. The (sum, n) => sum+n function needs the current sum and n.

That means you can distribute the work. Run each on a separate Lambda in parallel. Thousands at a time.

You go from a slow algorithm to as fast as a single operation, known as Amdahl's Law. With infinite scale, you could process an array of 10,000,000 elements almost as fast as an array of 10.

Lambda limits you to 1000 parallel invocations. Individual steps can be slow (like when transcoding video) and you're limited by the reduce step.

Performance is best when reduce is un-necessary. Performance is worst when reduce needs to iterate over every element in 1 call and can't be distributed.

Our adder is commutative and we can parallelize the reduce step using chunks of data.

In practice you'll find transformations that don't need a reduce step or require many maps. All follow this basic approach. :)

For the comp sci nerds 👉 this has no impact on big-O complexity. You're changing real-world performance, not the algorithm.

Build a distributed data processing pipeline

Let's build that adder and learn how to construct a robust massively distributed data processing pipeline. We're keeping the operation simple so we can focus on the architecture.

Here's the JavaScript code we're distributing:

const result = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5] // input array.map((n) => n * 2) // multiply each by 2.reduce((sum, n) => sum + n, 0) // sum together

Following principles from the Architecture Principles chapter, we're building a system that is:

- easy to understand

- robust against errors

- debuggable

- replayable

- always inspectable

We're going to use 3 Serverless Elements to get there:

- lambdas

- queues

- storage

You can see the full code on GitHub.

The elements

We're using 3 lambdas, 2 queues, and 2 DynamoDB tables.

3 Lambdas

sumArrayis our API-facing lambda. Accepts a request and kicks off the processtimesTwois the map lambda. Accepts a number, multiplies by 2, and triggers the next step.reducecombines intermediary steps into the final result. It's the most complex.

Our lambdas are written in TypeScript and each does 1 part of the process.

2 Queues

TimesTwoQueueholds messages fromsumArrayand callstimesTwo.ReduceQueueholds messages fromtimesTwoand callsreduce, which also uses the queue to trigger itself.

We're using SQS – Simple Queue Service – queues for their reliability. An SQS queue stores messages for up to 14 days and keeps retrying until your Lambda succeeds.

When something goes wrong there's little chance a message gets lost unless you're eating errors. If your code doesn't throw, SQS interprets that as success.

You can configure max retries and how long a message should stick around. When it exceeds those deadlines, you can configure a Dead Letter Queue to store the message.

DLQ's are useful for processing bad messages. Send an alert to yourself, store it in a different table, debug what's going on.

2 tables

scratchpad tablefor intermediary results fromtimesTwo. This table makesreduceeasier to implement and debug.sums tablefor final results

Step 1 – the API

You first need to get data into the system. We use a Serverless REST API.

# serverless.ymlfunctions:sumArray:handler: dist/sumArray.handlerevents:- http:path: sumArraymethod: POSTcors: trueenvironment:timesTwoQueueURL:Ref: TimesTwoQueue

sumArray is an endpoint that accepts POST requests and pipes them into the sumArray.handler function. We set the URL for our TimesTwoQueue as an environment variable.

Define the queue like this:

# serverless.ymlresources:Resources:TimesTwoQueue:Type: "AWS::SQS::Queue"Properties:QueueName: "TimesTwoQueue-${self:provider.stage}"VisibilityTimeout: 60

It's an SQS queue postfixed with the current stage, which helps us split between production and development.

The VisibilityTimeout says that when your Lambda accepts a message, it has 60 seconds to process. After that, SQS assumes you never received the message and tries again.

Distributed systems are fun like that.

The sumArray.ts Lambda that accepts requests looks like this:

// src/sumArray.tsexport const handler = async (event: APIGatewayEvent): Promise<APIResponse> => {const arrayId = uuidv4()if (!event.body) {return response(400, {status: "error",error: "Provide a JSON body",})}const array: number[] = JSON.parse(event.body)// split array into elements// trigger timesTwo lambda for each entryfor (let packetValue of array) {await sendSQSMessage(process.env.timesTwoQueueURL!, {arrayId,packetId: uuidv4(),packetValue,arrayLength: array.length,packetContains: 1,})}return response(200, {status: "success",array,arrayId,})}

Get API request, create an arrayId, parse JSON body, iterate over the input, return success and the new arrayId. Consumers can later use this ID identify their result.

Triggering the next step

We turn each element of the input array into a processing packet and send it to our SQS queue as a message.

// src/sumArray.tsfor (let packetValue of array) {await sendSQSMessage(process.env.timesTwoQueueURL!, {arrayId,packetId: uuidv4(),packetValue,arrayLength: array.length,packetContains: 1,})}

Each packet contains:

arrayIdto identify which input it belongs topacketIdto identify the packet itselfpacketValueas the value. You could use this to store entire JSON blobs.arrayLengthto helpreduceknow how many packets to expectpacketContainsto helpreduceknow when it's done

Most properties are metadata to help our pipeline. packetValue is the data we're processing.

sendSQSMessage is a helper method that sends an SQS message using the AWS SDK.

Step 2 – the map

Our map uses the timesTwo lambda and handles each packet in isolation.

# serverless.ymlfunctions:timesTwo:handler: dist/timesTwo.handlerevents:- sqs:arn:Fn::GetAtt:- TimesTwoQueue- ArnbatchSize: 1environment:reduceQueueURL:Ref: ReduceQueue

timesTwo handles events from the TimesTwoQueue using the timesTwo.handler method. It gets the reduceQueueURL as an environment variable to trigger the next step.

AWS and SQS call our lambda and keep retrying when something goes wrong. Perfect to let you re-deploy when there's a bug ✌️

The lambda looks like this:

// src/timesTwo.tsexport const handler = async (event: SQSEvent) => {// grab messages from queue// depending on batchSize there could be multiplelet packets: Packet[] = event.Records.map((record: SQSRecord) =>JSON.parse(record.body))// iterate packets and multiply by 2// this would be a more expensive operation usuallypackets = packets.map((packet) => ({...packet,packetValue: packet.packetValue * 2,}))// store each result in scratchpad table// in theory it's enough to put them on the queue// an intermediary table makes the reduce step easier to implementawait Promise.all(packets.map((packet) =>db.updateItem({TableName: process.env.SCRATCHPAD_TABLE!,Key: { arrayId: packet.arrayId, packetId: packet.packetId },UpdateExpression:"SET packetValue = :packetValue, arrayLength = :arrayLength, packetContains = :packetContains",ExpressionAttributeValues: {":packetValue": packet.packetValue,":arrayLength": packet.arrayLength,":packetContains": packet.packetContains,},})))// trigger next step in calculationconst uniqueArrayIds = Array.from(new Set(packets.map((packet) => packet.arrayId)))await Promise.all(uniqueArrayIds.map((arrayId) =>sendSQSMessage(process.env.reduceQueueURL!, arrayId)))return true}

Accept an event from SQS, parse JSON body, do the work, store intermediary results, trigger reduce step for each input.

SQS might call your lambda with multiple messages depending on your batchSize config. This helps you optimize cost and find the right balance between the number of executions and execution time.

Trigger the next step

Triggering the next step happens in 2 parts

- store intermediary result

- trigger next lambda

Storing intermediary results makes implementing the next lambda easier. We're building a faux queue on top of DynamoDB. That's okay because it makes the system easier to debug.

Something went wrong? Check intermediary table, see what's up.

We iterate over results, fire a DynamoDB updateItem query, and await the queries.

// src/timesTwo.ts// store each result in scratchpad table// in theory it's enough to put them on the queue// an intermediary table makes the reduce step easier to implementawait Promise.all(packets.map((packet) =>db.updateItem({TableName: process.env.SCRATCHPAD_TABLE!,Key: { arrayId: packet.arrayId, packetId: packet.packetId },UpdateExpression:"SET packetValue = :packetValue, arrayLength = :arrayLength, packetContains = :packetContains",ExpressionAttributeValues: {":packetValue": packet.packetValue,":arrayLength": packet.arrayLength,":packetContains": packet.packetContains,},})))

Each entry in this table is uniquely identified with a combination of arrayId and packetId.

Triggering the next step happens in another loop.

// src/timesTwo.ts// trigger next step in calculationconst uniqueArrayIds = Array.from(new Set(packets.map((packet) => packet.arrayId)))await Promise.all(uniqueArrayIds.map((arrayId) =>sendSQSMessage(process.env.reduceQueueURL!, arrayId)))

We use an ES6 Set to get a list of unique array ids from our input message. You never know what gets jumbled up on the queue and you might receive multiple inputs in parallel.

Distributed systems are fun :)

For each unique input, we trigger a reduce lambda via ReduceQueue. A single reduce stream makes this example easier. You should aim for parallelism in production.

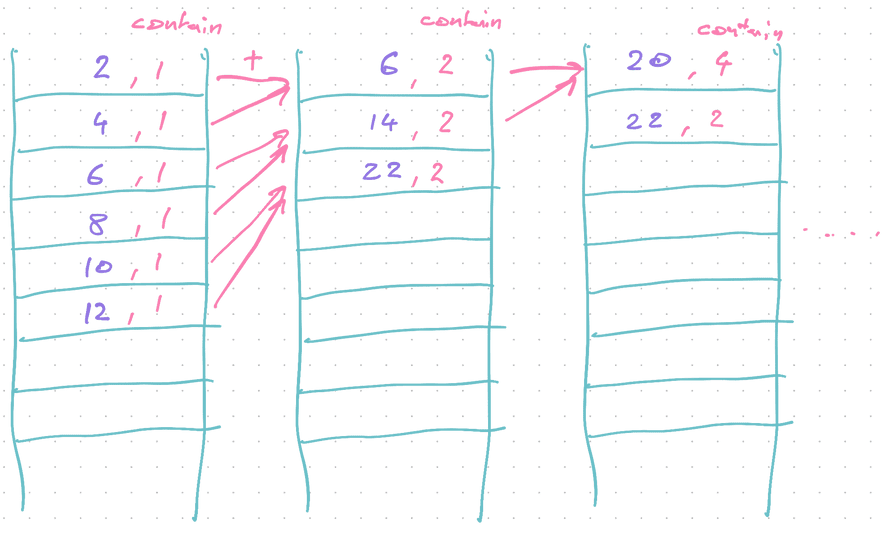

Step 3 – reduce

Combining intermediary steps into the final result is the most complex part of our example.

The simplest approach is to take the entire input and combine in 1 step. With large datasets this becomes impossible. Especially if combining elements is a big operation.

You could combine 2 elements at a time and run the reduce step in parallel.

Fine-tuning for number of invocations and speed of execution will result in an N somewhere between 2 and All. Optimal numbers depend on what you're doing.

Our reduce function uses the scratchpad table as a queue:

- Take 2 elements

- Combine

- Write the new element

- Delete the 2 originals

Like this:

At each invocation we take 2 packets:

{arrayId: // ...packetId: // ...packetValue: 2,packetContains: 1,arrayLength: 10}{arrayId: // ...packetId: // ...packetValue: 4,packetContains: 1,arrayLength: 10}

And combine them into a new packet

// +{arrayId: // ...packetId: // ...packetValue: 6packetContains: 2,arrayLength: 10}

When the count of included packets – packetContains – matches the total array length – arrayLength – we know this is the final result and write it into the results table.

Like I said, this is the complicated part.

The reduce step code

In code, the reduce step starts like any other lambda:

// src/reduce.tsexport const handler = async (event: SQSEvent) => {// grab messages from queue// depending on batchSize there could be multiplelet arrayIds: string[] = event.Records.map((record: SQSRecord) =>JSON.parse(record.body))// process each ID from batchawait Promise.all(arrayIds.map(reduceArray))}

Grab arrayIds from the SQS event and wait until every reduceArray call is done.

Then the reduceArray function does its job:

// src/reduce.tsasync function reduceArray(arrayId: string) {// grab 2 entries from scratchpad table// IRL you'd grab as many as you can cost-effectively process in execution// depends what you're doingconst packets = await readPackets(arrayId)if (packets.length > 0) {// sum packets togetherconst sum = packets.reduce((sum: number, packet: Packet) => sum + packet.packetValue,0)// add the new item sum to scratchpad table// we do this first so we don't delete rows if it failsconst newPacket = {arrayId,packetId: uuidv4(),arrayLength: packets[0].arrayLength,packetValue: sum,packetContains: packets.reduce((count: number, packet: Packet) => count + packet.packetContains,0),}await db.updateItem({TableName: process.env.SCRATCHPAD_TABLE!,Key: {arrayId,packetId: uuidv4(),},UpdateExpression:"SET packetValue = :packetValue, arrayLength = :arrayLength, packetContains = :packetContains",ExpressionAttributeValues: {":packetValue": newPacket.packetValue,":arrayLength": newPacket.arrayLength,":packetContains": newPacket.packetContains,},})// delete the 2 rows we just summedawait cleanup(packets)// are we done?if (newPacket.packetContains >= newPacket.arrayLength) {// done, save sum to final tableawait db.updateItem({TableName: process.env.SUMS_TABLE!,Key: {arrayId,},UpdateExpression: "SET resultSum = :resultSum",ExpressionAttributeValues: {":resultSum": sum,},})} else {// not done, trigger another reduce stepawait sendSQSMessage(process.env.reduceQueueURL!, arrayId)}}}

Gets 2 entries from the DynamoDB table2 and combines them into a new packet.

This packet must have a new packetId. It's a new entry for the faux processing queue on DynamoDB.

Insert that back. If it succeeds, remove the previous 2 elements using their arrayId/packetId combination.

If our new packetContains is greater than or equal to the total arrayLength, we know the computation is complete. Write results to the final table.

Conclusion

Lambda processing pipelines are a powerful tool that can process large amounts of data in near real-time. I have yet to find a way to swamp one of these in production.

Slow downs happen where you have to introduce throttling to limit processing because a downstream system can't take the load.

✌️

Next chapter, we talk about monitoring serverless apps.

- Our dataloss happened because of Postgres. Sometimes it would fail to insert a row, but wouldn't throw an error. We mitigated with various workarounds but a small loss remained. At that point we decided it was good enough.↩

- We use a

Limit: 2argument to limit how much of the table we scan through. Don't need more than 2, don't read more than 2. Keeps everything snappy↩