Robust backend design

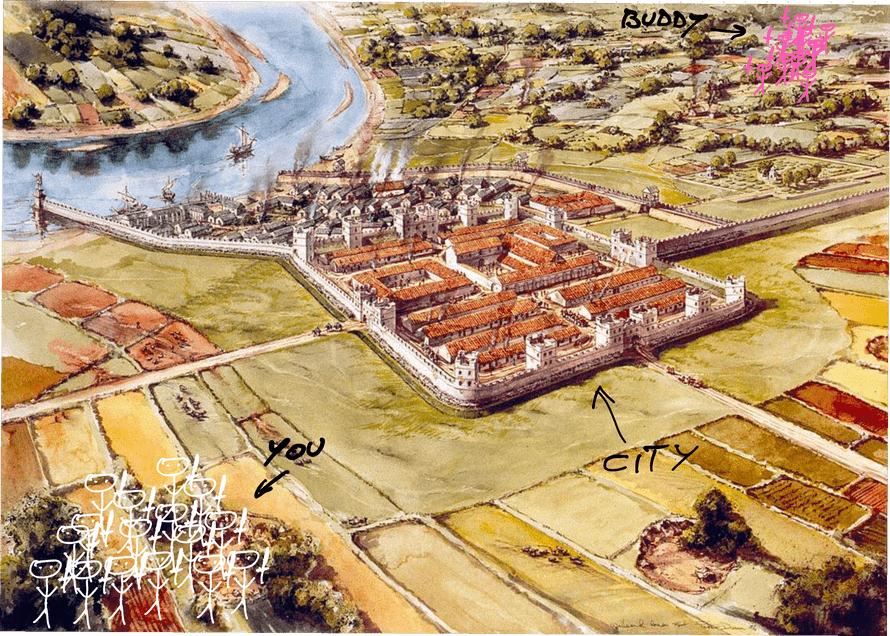

Imagine you're a Roman general leading a vast and powerful army. You're about to attack a city.

But you can't do it alone.

Your buddy with another vast and powerful army hides behind a hill on the other side. You need their help to win.

Attack together and win. Attack alone and die.

How do you ensure a joint attack?

Smoke signals would reveal your plan to the city. It's too far to shout and phones are 2000 years in the future.

A messenger is your best bet. Run to the other army, deliver the message, come back with confirmation.

Unless they're caught. 🤔

The messenger could fail to deliver your message. Or get caught on their way back. You'll never know.

Send more messengers until one makes it back? How does your friend know that any messenger made it back? Nobody wants to attack alone.

This puzzle is known as the Two Generals' Problem. There is no solution.

No algorithm guarantees 100% certainty over a lossy medium. Best you can do is "Pretty sure."

And that's why distributed systems are hard.

You cannot have 100% reliability. As soon as servers talk to each other, you're doomed to probabilities.

Serverless systems are always distributed. 😅

Build a robust backend

A robust backend keeps working in the face of failure.

As we mentioned in the Architecture Principles chapter, your backend follows 3 principles:

- Everything can and will fail

- Your system should keep working

- Failures should be easy to fix

You get there with a combination of error recovery, error isolation, and knowing when your system needs help.

The strategies mentioned in Architecture Principles were:

- isolate errors

- retry until success

- make operations replayable

- be debuggable

- remove bad requests

- alert the engineer when something's wrong

- control your flow

This chapter talks about how.

Isolate errors

In March 2017, Amazon S3 went down and took with it half the internet. Root cause was a typo.

AWS Engineers were testing what happens when a few servers go offline. A typo took out too many and the rest got overwhelmed. They started failing one by one.

Soon the whole system was down.

And because AWS relies on S3 to store files ... much of AWS went down. And because half the internet runs on AWS ... it went down.

AWS couldn't even update their status dashboard because error icons live on S3.

To isolate errors you have to reduce inter-dependency. Always think: "What can I do to make moving pieces less dependent on each other?"

In your car, the brakes keep working even if your brake lights go out. The systems work together, but independently.

Inter-dependency can be subtle and hard to spot. The specifics are different each time.

Here are 3 rules:

- Give each operation a single responsibility

- Do the whole operation in one atomic go

- Avoid coupling

Serverless functions are optimized for this approach by default. They encourage you to keep code light and isolated 🤘

Give each operation a single responsibility

Think of serverless code like a function. How big are your functions? How much do they do?

Say you were building a basic math module. Would you write a function that performs plus and minus?

function doMath(a: number, b: number, op: "plus" | "minus") {if (op === "plus") {return a + b} else {return a - b}}

That looks odd to me. Plus and minus are distinct operations.

You'd write 2 functions instead:

function plus(a: number, b: number) {return a + b}function minus(a: number, b: number) {return a - b}

That's easier to work with.

Splitting your code into small operations is an art. Big functions are hard to debug and too many small functions are hard to understand.

My rule is that when I use "and" to describe a function, I need a new function.

Do the whole operation in one atomic go

Atomic operations guarantee correctness. Perform an action start to finish without distraction.

Say you're taking an important memory medicine.

You grab the pill bottle, take out a pill, put it on your desk, get an email and start reading. You elbow the pill off your desk.

10 minutes later you look down and there's no pill. Did you take it?

Same thing happens when your lambdas do too much. Your code can get distracted, halfway failures happen, and you're left with a corrupt state.

Recovering from corrupt state is hard.

Instead, try to avoid distractions. Keep operations small, go start to finish, delegate. Let another process read email. And clean up when there's an error.

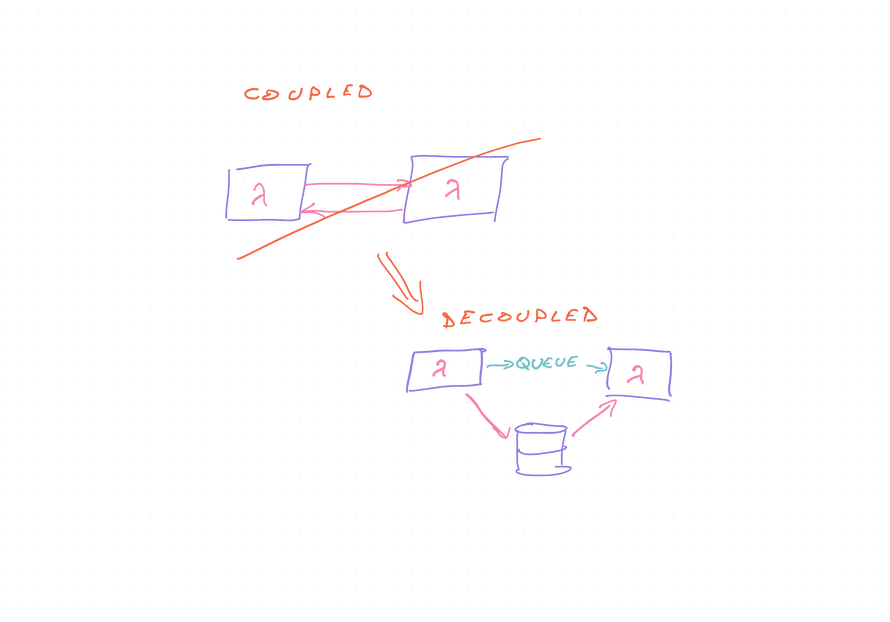

Avoid coupling

With atomic operations and delegating heavy work to other functions, you're primed for another mistake: Direct dependency.

Like this:

function myLambda() {// read from db// prep the thingawait anotherLambda(data)// save the stuff}

You're coupling your myLambda function to your anotherLambda function. If anotherLambda fails, the whole process fails.

Try decoupling these with a queue. Turn it into a process. myLambda does a little, pushes to the queue, anotherLambda does the rest.

You can see this principle in action in the Lambda Pipelines for distributed data processing chapter.

Retry until success

Retrying requests is built into the serverless model.

AWS retries every lambda invocation, if the call fails. The number of retries depends on who's calling.

API Gateway is proxying requests from users and that makes retries harder than an SQS queue which has all the time in the world.

Retries happen for two reasons:

- Lambda never got the message

- Lambda failed to process the message

#1 is out of your control. Two generals problem struck between request and your code. 💩

#2 means you should always throw an error when something goes wrong. Do not pretend.

Both SQS – Simple Queue Service – and SNS – Simple Notification Service – support retries out of the box. They're the most common ways AWS services communicate.

Details on how each implements retries differ. You can read more about How SNS works and How SQS works in AWS docs.

Both follow this pattern:

- Message accepted into SQS / SNS

- Message stored in multiple locations

- Message sent to your lambda

- Wait for lambda to process or fail

- If processed, remove message

- If failed, retry ... sometimes thousands of times

Wait to delete the message until after confirmation. You might lose data otherwise.

Keep this in mind: never mark something as processed until you know for sure ✌️

Build replayable operations

Your code can retry for any reason. Make sure that's not a problem.

Follow this 4 step algorithm:

- Verify work needs doing

- Do the work

- Mark work as done

- Verify marking it done worked

Two Generals Problem may strike between you and your database 😉

In pseudocode, functions follow this pattern:

function processMessage(messageId) {let message = db.get(messageId)if (!message.processed) {try {doTheWork(message)} catch (error) {throw error}message.processed = truedb.save(message)if (db.get(messageId).processed) {return success} else {throw "Processing failed"}}return success}

This guards against all failure modes:

- Processing retried, but wasn't needed

- Work failed

- Saving work failed

Make sure doTheWork throws an error, if it fails to save. Common cause of spooky dataloss. ✌️

Be debuggable

Debugging distributed systems is hard. More art than science.

You'll need to know or learn your system inside-out. Tease it apart bit by bit.

Keeping your code re-runnable helps. Keeping your data stored helps. Having easy access to all this helps.

When debugging distributed systems I like to follow this approach:

- Look at the data

- Find which step of the process failed

- Get the data that failed

- Run the step that failed

- Look at logs

You can use a debugger to step through your code locally. With a unit test using production data. But it's not the same as a full production environment.

If local debugging fails, add logs. Many logs. Run in production, see what happens.

Being debuggable therefore means:

- Safely replayable operations

- Keep intermediate data long enough

- Manually executable with specific requests

- Identifiable and traceable requests (AWS adds requestId to every log)

- Locally executable for unit testing

Remove bad requests

Requests can include a poison pill – a piece of bad data you can never process. They might swamp your system with infinite retries.

Say you want to process requests in sequence.

9 requests go great, the 10th is a poison pill. Your code gets stuck trying and retrying for days.

Meanwhile users 11 to 11,000 storm your email crying that the service is down. But it's not down, it's stuck.

Dead letter queues can help. They hold bad messages until you have time to debug.

Each queue-facing Lambda gets two queues:

- The trigger queue

- A dead letter queue for bad requests

Like this in serverless.yml:

# serverless.ymlfunctions:worker:handler: dist/lambdas/worker.handlerevents:# triggering from SQS events- sqs:arn:Fn::GetAtt:- WorkerQueue- ArnbatchSize: 1resources:Resources:WorkerQueue:Type: "AWS::SQS::Queue"Properties:QueueName: "WorkerQueue-${self:provider.stage}"# send to deadletter after 10 retriesRedrivePolicy:deadLetterTargetArn:Fn::GetAtt:- WorkerDLQueue- ArnmaxReceiveCount: 10WorkerDLQueue:Type: "AWS::SQS::Queue"Properties:QueueName: "WorkerDLQueue-${self:provider.stage}"# keep messages for a long time to help debugMessageRetentionPeriod: 1209600 # 14 days

A worker lambda runs from an SQS queue. When it fails, messages are retried.

Now all you need is an alarm on dead letter queue size to say "Hey something's wrong, you should check".

Bug in your code? Fix the bug, re-run worker from dead letter queue. No messages are lost.

Bad messages? Drop 'em like it's hot.

Alert an engineer

The challenge with serverless systems is that you can't see what's going on. And you're not sitting there staring at logs.

You need a monitoring system. A way to keep tabs on your services and send alerts. Email for small problems, slack for big problems, text message for critical problems.

That's what works for me.

AWS has basic monitoring built-in, Datadog is great for more control. More on monitoring in the Monitoring serverless apps chapter

Control your flow

Control your flow means looking at the performance of your system as a whole.

Writing fast code is great, but if your speedy lambda feeds into a slow lambda, you're gonna have a bad day. Work piles up, systems stop, customers complain.

You want to ensure a smooth flow through the whole system.

Computer science talks about this through Queuing theory and stochastic modeling. Business folk talk about Theory of constraints.

It's a huge field :)

We talk more about flow in the Serverless performance chapter.

Conclusion

In conclusion, a distributed system is never 100% reliable. You can make it better with small replayable operations, keeping code debuggable, and removing bad requests.

Next chapter we look at where to store your data.